DB Design Step by Step: From Requirements to Production Systems

Designing a database is an engineering discipline that defines how data is structured, constrained, stored, accessed, and governed within a database system. It determines how information is modeled at the conceptual level, formalized at the logical level, and implemented at the physical level inside a DBMS architecture.

Structural design must be distinguished from analytical system architectures, where the separation between operational databases and analytical platforms is formally defined in the database vs data warehouse article.

A database design is not a diagramming exercise. It is a systems-engineering process that integrates data modeling, workload analysis, integrity constraints, performance engineering, security controls, and lifecycle governance into a coherent data architecture.

Test Real Analytical Workloads with Exasol Personal

Unlimited data. Full analytics performance.

In analytical environments, system structure extends beyond schema design into multi-layer architectures that integrate ingestion, storage, governance, and analytics processing within a unified data warehouse architecture.

Effective database design aligns data structures with:

- access patterns

- query execution models

- transaction semantics

- consistency guarantees

- scalability requirements

- operational constraints

The design process spans the full lifecycle of a system: from requirements engineering and conceptual modeling to physical storage design, performance optimization, deployment, and long-term schema evolution. These structural foundations build directly on core database concepts such as data models, schemas, constraints, and query semantics.

Database Design in DBMS

Database design in a DBMS context refers to the formal process of defining data structures, relationships, constraints, and storage models that govern how data is represented and processed inside a database system.

It operates across three abstraction layers:

- Conceptual layer → defines meaning and relationships of data independent of technology

- Logical layer → defines schemas, entities, attributes, and constraints within a data model

- Physical layer → defines storage structures, indexing strategies, partitioning, and data placement

Within a DBMS architecture, db design functions as the structural foundation that determines:

- how queries are executed

- how transactions are isolated

- how data integrity is enforced

- how concurrency is managed

- how performance scales

- how storage is optimized

In relational systems, the relational model formalizes structure and independence assumptions that shape how schemas and constraints are represented.

Db design is therefore not isolated from execution engines, optimizers, or storage layers. It directly influences query planning, indexing efficiency, memory utilization, I/O behavior, and concurrency control.

Database Design vs Data Modeling

Data modeling defines what data represents.

Database design defines how that data is structured, constrained, stored, and operated.

Conceptual modeling

Defines entities, relationships, semantics, and meaning without implementation constraints.

Logical modeling

Defines schemas, tables, attributes, relationships, keys, and constraints within a formal data model.

Physical modeling

Defines storage formats, indexing structures, partitioning strategies, and data placement in the storage engine.

Database design integrates all three layers into a coherent system architecture, ensuring that semantic correctness, structural integrity, and operational performance are aligned.

Designing a Database: Objectives

Database design is governed by a defined set of engineering objectives that function as structural constraints. These objectives determine how a system behaves under operational load, not how it appears in documentation.

Data integrity ensures that stored information remains structurally valid, semantically correct, and logically consistent across all operations. Integrity is enforced through schema constraints, key structures, validation rules, and transactional guarantees rather than application-layer logic.

Scalability defines the system’s capacity to absorb growth in data volume, workload complexity, and user concurrency without requiring architectural redesign. Scalability requirements directly influence schema topology, partitioning strategies, indexing models, and storage distribution.

Test Real Analytical Workloads with Exasol Personal

Unlimited data. Full analytics performance.

Performance is determined by access patterns, query execution models, indexing structures, memory utilization, and data locality. Design decisions at the logical and physical layers define I/O behavior, cache efficiency, execution cost, and concurrency throughput.

Consistency governs correctness under concurrent access. It is implemented through transactional semantics, isolation models, locking strategies, and concurrency control mechanisms embedded in the DBMS architecture.

Maintainability determines the system’s ability to evolve without destabilization. Schema evolution, versioning models, migration strategies, and backward compatibility mechanisms are design-level responsibilities, not operational fixes.

Security is enforced structurally through access control models, privilege separation, authentication layers, authorization policies, and exposure boundaries defined at the schema and system architecture level.

Compliance is achieved through auditable data structures, traceability models, access logging, lineage tracking, and governance frameworks embedded in the design itself.

These objectives are interdependent. Database design is not the optimization of a single dimension, but the formal balancing of competing constraints within a coherent system architecture.

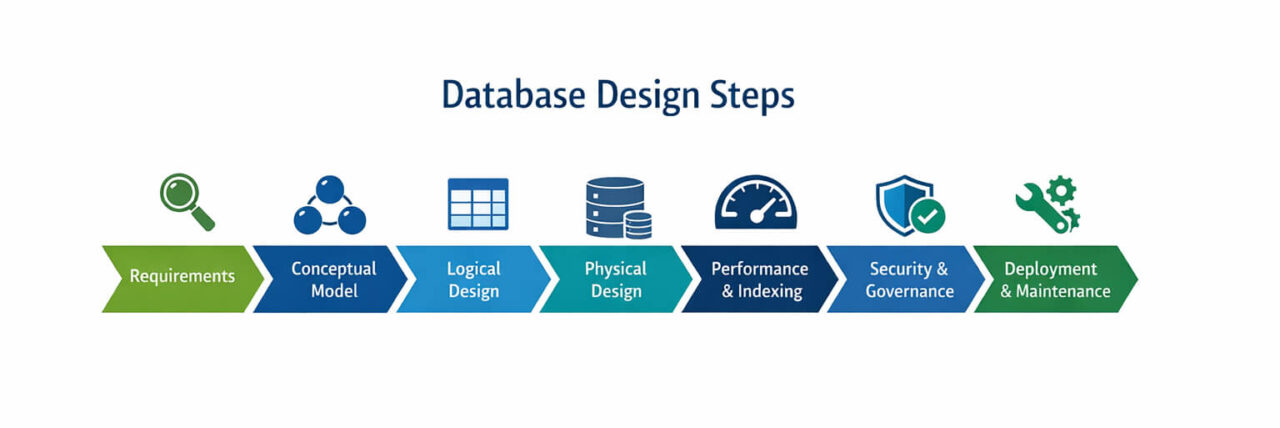

Step-by-Step Framework

Database Design Steps

This process model represents the formal lifecycle of database design as a structured engineering sequence. Each stage defines a distinct architectural responsibility and constraint domain. The sequence is logical, not linear; feedback loops and iteration occur across all phases.

1. Requirements analysis

Defines functional scope, data semantics, workload characteristics, access patterns, regulatory constraints, and operational boundaries. This stage establishes the constraint model that governs all downstream design decisions.

2. Conceptual modeling

Defines entities, relationships, cardinality, and semantic structure independently of implementation technology. This stage establishes meaning and domain coherence.

3. Logical schema design

Translates conceptual structures into formal schemas, defining tables, attributes, relationships, and constraints within a data model. Structural correctness and semantic integrity are established here.

4. Normalization

Applies structural dependency rules to eliminate redundancy, update anomalies, and integrity risks. This stage enforces formal consistency and correctness in schema structure.

5. Key design

Defines identity models, relational anchoring, and integrity boundaries through primary keys, foreign keys, and identity strategies. This stage establishes structural identity and relational stability.

6. Physical schema design

Defines storage layouts, file structures, page organization, and data placement models. This stage translates logical structure into physical representation.

7. Indexing strategy

Defines access paths, query acceleration structures, and execution optimization models based on workload characteristics and access patterns.

8. Partitioning strategy

Defines data segmentation, distribution models, and scalability boundaries through horizontal partitioning, vertical partitioning, and sharding architectures.

9. Security modeling

Defines access control structures, privilege boundaries, identity models, and exposure constraints embedded in schema and system architecture.

10. Performance modeling

Defines execution behavior, memory utilization, concurrency characteristics, and workload distribution across system resources.

11. Testing

Validates correctness, integrity, performance stability, and constraint enforcement under realistic workload conditions.

12. Deployment

Transitions the system from design state to operational state, including data initialization, configuration, and system integration.

13. Monitoring

Establishes observability, performance tracking, integrity validation, and operational health measurement.

14. Evolution

Defines controlled schema evolution, system adaptation, structural refactoring, and long-term architectural sustainability.

Each stage below decomposes these steps into the corresponding design layer, from DBMS fundamentals through production lifecycle management.

Requirements Analysis

Requirements engineering defines the structural and operational constraints that shape the entire database architecture. It establishes the boundary conditions within which all modeling, schema design, and physical optimization decisions must operate.

Business requirements define the functional scope of the system: what information must be represented, which processes depend on it, and which operations must be supported. These requirements determine domain entities, data semantics, and structural boundaries.

Data requirements define the nature of the information itself: data types, relationships, cardinality, lifecycle, retention, and governance constraints. These requirements shape schema structure and constraint models.

Query patterns describe how data is accessed rather than how it is stored. Read frequency, write frequency, aggregation behavior, join complexity, filtering patterns, and access locality determine indexing strategies, schema topology, and storage layout.

Workload classification differentiates between operational workloads and analytical workloads. Transaction-heavy systems, read-optimized systems, and hybrid systems impose fundamentally different structural constraints on schema design, indexing, and partitioning.

Read/write patterns define contention models and concurrency pressure. High-write systems require different key strategies, partitioning models, and locking behavior than read-dominant systems.

Latency constraints define performance boundaries. Real-time systems, near-real-time systems, and batch systems require different execution models, caching strategies, and data locality designs.

Requirements analysis is not documentation. It is the formal translation of operational reality into structural constraints that govern the database architecture.

Test Real Analytical Workloads with Exasol Personal

Unlimited data. Full analytics performance.

Stakeholder Mapping

Database design exists at the intersection of multiple organizational domains. Each domain imposes distinct structural constraints on the system.

Business stakeholders define semantic meaning, reporting needs, and functional boundaries. Their requirements shape entity definitions, domain models, and semantic relationships.

Engineering stakeholders define system constraints, integration models, scalability requirements, and operational reliability targets. Their requirements shape schema topology, partitioning strategies, and performance models.

Analytics stakeholders define data consumption patterns, aggregation requirements, historical retention, and analytical modeling needs. Their requirements shape dimensional modeling, indexing strategies, and data access structures.

Compliance stakeholders define regulatory boundaries, data governance models, retention rules, auditability requirements, and access controls. Their requirements shape schema design, logging structures, and governance architecture.

Requirements engineering aligns these domains into a unified constraint model that governs the entire design process.

Conceptual Design

Conceptual Data Modeling

Conceptual design defines the semantic structure of a system independently of implementation technology. It establishes what data represents, how entities relate, and which relationships are structurally meaningful before any schema or storage decisions are introduced.

Entity identification defines the core objects of the domain. Entities represent stable concepts rather than transient states. Each entity is defined by its semantic identity, not by how it will be stored.

Relationship modeling defines how entities interact. Relationships encode dependencies, ownership, association, and interaction patterns within the domain. These relationships determine structural coupling across the system.

Cardinality defines quantitative constraints between entities. One-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many relationships impose fundamentally different structural requirements on later schema design.

Optionality defines existence constraints. Mandatory and optional relationships define dependency boundaries and determine whether entities can exist independently or only within relational context.

Conceptual modeling isolates semantic correctness from technical optimization. It ensures that structural meaning is preserved before performance, storage, and execution concerns are introduced.

ER Modeling

Entity–Relationship modeling formalizes conceptual structures into a consistent representation model. It provides a structural language for defining entities, attributes, and relationships without embedding physical implementation constraints. The entity-relationship model provides a formal conceptual representation of entities and relationships before translation into logical schemas.

Entity–Relationship diagrams represent semantic structures visually while preserving formal consistency rules. They function as abstraction tools, not storage designs.

Relationship types define structural coupling:

- associative relationships

- hierarchical relationships

- recursive relationships

- dependent relationships

Each relationship type introduces different constraint patterns that propagate into logical schema design.

Weak entities depend on parent entities for identity and existence. Their lifecycle is structurally bound to another entity through identifying relationships.

Strong entities maintain independent identity and existence boundaries. They define autonomous structural units within the domain model.

ER modeling provides structural clarity, constraint definition, and semantic consistency. It ensures that the system’s meaning layer is formally defined before translation into logical schemas and physical storage structures.

Logical Design

Logical Schema Design

Logical design translates conceptual models into formal data structures. It defines how entities, relationships, and attributes are represented within a data model while remaining independent of physical storage implementation.

Table structures define structural boundaries between data domains. Each table represents a distinct entity or relationship abstraction with a defined semantic scope. Structural separation is driven by meaning and dependency, not by performance optimization.

Attribute modeling defines the properties of entities. Attributes are defined by:

- semantic meaning

- domain constraints

- data type boundaries

- nullability rules

- validation conditions

Attributes represent semantic facts, not derived values or computed states.

Domain constraints define allowable value ranges and semantic validity. They enforce correctness at the schema level rather than through application logic. Domain modeling ensures that invalid states cannot be represented structurally.

Logical schema design establishes formal structure, semantic correctness, and constraint integrity before physical optimization is introduced.

In complex environments where data resides across heterogeneous systems or analytic layers, support for virtual schemas may influence how logical structures are modeled and integrated without duplicating source data.

Normalization

Normalization defines structural rules for eliminating redundancy, dependency anomalies, and update inconsistencies. It is a formal method for enforcing data integrity and structural consistency.

First Normal Form (1NF)

Ensures atomicity of values and eliminates repeating groups. Each attribute contains indivisible values and each record is uniquely identifiable.

Second Normal Form (2NF)

Eliminates partial dependencies. Non-key attributes depend on the full primary key rather than a subset of it.

Third Normal Form (3NF)

Eliminates transitive dependencies. Non-key attributes depend only on the primary key and not on other non-key attributes.

Boyce–Codd Normal Form (BCNF)

Strengthens functional dependency constraints. Every determinant must be a candidate key, eliminating structural anomalies not addressed by 3NF.

Normalization defines structural correctness. It does not define performance optimization. Denormalization is a controlled physical design decision, not a conceptual or logical compromise.

Keys

Keys define identity, integrity, and relational structure within a schema. They function as structural anchors for all relational operations.

Primary keys define entity identity. They provide uniqueness, stability, and referential anchoring. Primary keys are structural identifiers, not business semantics.

Foreign keys define relational integrity. They enforce dependency relationships between entities and define relational structure across the schema.

Natural keys use domain attributes as identifiers. They embed business semantics into identity models and impose stability risks when domain values change.

Surrogate keys use system-generated identifiers. They decouple identity from semantics and provide structural stability at the cost of semantic opacity.

Key design defines identity boundaries, relationship stability, and integrity enforcement across the system.

Physical Design

Physical Schema Design

Physical design defines how logical structures are materialized inside the storage and execution layers of a DBMS. It translates schemas into concrete storage layouts, access paths, and data placement strategies.

Storage layout defines how data is organized on persistent media. It determines physical locality, access efficiency, and I/O behavior. Storage layout influences cache efficiency, prefetching behavior, and sequential access performance.

File structures define how records are grouped, ordered, and accessed at the storage layer. Heap files, clustered storage, append-only structures, and columnar layouts impose different access patterns and performance characteristics.

Page structures define the atomic units of storage and retrieval. Page size, record placement, and block organization influence I/O amplification, buffer management efficiency, and concurrency behavior.

Physical schema design establishes the mechanical foundation of data access. It determines how efficiently data can be located, loaded, and processed by the execution engine.

Test Real Analytical Workloads with Exasol Personal

Unlimited data. Full analytics performance.

Indexing Strategy

Indexing defines the primary access paths through the data. It is not an optimization layer; it is a structural component of physical design.

B-tree indexes provide ordered access paths and support range queries, sorting operations, and ordered scans. They define predictable performance characteristics for transactional and analytical workloads.

Hash indexes provide constant-time access for equality-based lookups. They optimize point queries but provide no ordering semantics.

Composite indexes define multi-attribute access paths. Their effectiveness depends on attribute ordering, selectivity, and query structure.

Covering indexes embed query-relevant attributes within the index structure itself, eliminating the need for base table access and reducing I/O cost.

Cardinality-driven indexing uses data distribution and selectivity to determine index placement. Indexes are structural decisions based on access probability, not default configurations.

Indexing strategy defines query execution efficiency, memory utilization, and concurrency behavior. Over-indexing increases write amplification and maintenance cost. Under-indexing increases execution cost and latency.

Partitioning

Partitioning defines how data is segmented across storage and execution boundaries. It is a structural scalability mechanism, not a performance patch.

Horizontal partitioning divides data by rows based on key ranges, hashing functions, or semantic attributes. It controls data distribution, parallelism, and workload isolation.

Vertical partitioning divides data by columns. It separates frequently accessed attributes from infrequently accessed attributes, optimizing access locality and I/O behavior.

Sharding distributes partitions across independent nodes or storage domains. It defines system-level scalability, fault isolation, and parallel processing capacity.

Partitioning determines data locality, execution parallelism, fault domains, and scalability boundaries. It defines how the system grows structurally rather than how it is optimized incrementally.

Performance-Oriented Design

Performance Engineering

Performance-oriented design defines how efficiently a database system executes operations under real workload conditions. Performance is not an optimization phase; it is a structural property that emerges from design decisions at every layer of the architecture.

Query execution patterns determine how data is accessed, transformed, and returned. Sequential scans, indexed lookups, joins, aggregations, and subqueries impose different execution costs and memory behaviors. Schema structure and indexing models define whether execution is CPU-bound, memory-bound, or I/O-bound.

Performance validation requires reproducible workload modeling and controlled execution environments, where benchmarking frameworks such as reproducible database benchmarks provide structured evaluation of execution behavior under consistent conditions.

Join strategies define how relational data is combined. Nested-loop joins, hash joins, and merge joins each impose different memory requirements, data locality constraints, and execution characteristics. Data distribution, cardinality, and indexing directly influence join selection and performance stability.

Data locality determines how efficiently data can be accessed. Co-located data reduces I/O amplification and cache misses. Poor locality increases memory pressure, disk access, and network overhead in distributed systems.

Memory usage defines execution efficiency. Buffer management, caching strategies, and working-set size determine whether operations execute in-memory or spill to disk. Physical design and indexing structures define memory access patterns and cache behavior.

Concurrency control governs parallel execution. Locking models, isolation levels, and transaction coordination define throughput limits and contention behavior. Structural design decisions influence deadlock risk, blocking patterns, and execution scalability.

Performance engineering aligns schema design, indexing, storage layout, and execution models into a coherent performance architecture. It ensures that scalability and efficiency are properties of the system structure rather than outcomes of incremental tuning.

Test Real Analytical Workloads with Exasol Personal

Unlimited data. Full analytics performance.

Integrity and Consistency

Data Integrity

Data integrity defines the structural correctness and semantic validity of stored information. It ensures that all data states represented in the system are valid, consistent, and meaningful within the defined domain model.

Referential integrity enforces relational correctness across entities. Foreign key constraints define dependency structures and prevent the existence of orphaned records, broken relationships, and invalid references. Referential integrity is a schema-level enforcement mechanism, not an application responsibility.

Constraints define structural validity rules. Domain constraints, uniqueness constraints, check constraints, and not-null constraints prevent invalid states from being represented in the system. Constraints transform business rules into structural guarantees.

Transactions define atomic state transitions. They ensure that multi-step operations execute as indivisible units of work, preserving consistency under failure conditions and concurrent access.

ACID properties define the formal integrity model:

- Atomicity ensures all-or-nothing execution

- Consistency enforces valid state transitions

- Isolation prevents interference between concurrent operations

- Durability guarantees persistence of committed changes

Integrity and consistency are not features layered on top of a system. They are properties embedded in schema design, transaction models, and DBMS architecture.

They define the system’s reliability boundary: what states are representable, what transitions are valid, and what failures are survivable without corruption.

Security by Design

Security is a structural property of database architecture. It is defined by how data is modeled, how access boundaries are enforced, and how privileges are distributed across the system.

Access control models define who can access what data and under which conditions. Role-based access control, attribute-based access control, and policy-based models establish structural permission boundaries at the schema and system level.

Authentication defines identity verification mechanisms. Identity management is decoupled from data access logic and enforced through controlled identity layers rather than embedded credentials.

Authorization defines permission scope. Privilege separation, least-privilege models, and access segmentation ensure that users and services operate within strictly bounded capability domains.

Row-level security enforces fine-grained data isolation. It restricts data visibility at the record level based on identity context, policy rules, and execution scope.

Security by design ensures that exposure boundaries are structural, enforceable, and verifiable rather than procedural or policy-based.

Data Protection

Data protection defines how sensitive information is stored, accessed, and preserved across its lifecycle.

Encryption protects data confidentiality. Encryption mechanisms apply to data at rest, data in transit, and data in use, ensuring that exposure surfaces are minimized across all operational states.

Sensitive data handling defines classification models, access restrictions, masking strategies, and isolation boundaries for regulated or high-risk information.

Key management defines cryptographic trust models. Secure key storage, rotation policies, access separation, and lifecycle governance prevent systemic compromise through credential exposure.

Security and governance are not compliance layers. They are structural properties embedded in schema design, access models, and system architecture. They define trust boundaries, exposure limits, and operational safety constraints across the database system.

Design Patterns

They define repeatable structural models that align data organization with workload characteristics, execution models, and system objectives. Patterns are not templates; they are architectural abstractions that encode proven structural principles.

Database design patterns such as OLTP schemas, general OLAP structures, indexing strategies, and transactional consistency models are broader structural frameworks focused on how data is organized for system behavior, integrity, and operational performance. In contrast, data warehouse models optimize data arrangement for analytical processing, reporting, and dimensional analysis (they are analytics-layer specializations of those patterns).

OLTP schema

Transactional schemas are optimized for high-concurrency, write-intensive workloads. They prioritize normalization, referential integrity, and transactional consistency. Structural characteristics include:

- normalized table structures

- strict constraint enforcement

- high write throughput support

- low-latency point access patterns

- concurrency-safe key design

OLTP design emphasizes correctness, isolation, and consistency under concurrent access.

OLAP schema

Analytical schemas are optimized for read-heavy workloads, aggregation, and large-scale scans. They prioritize access efficiency, query performance, and analytical flexibility. Structural characteristics include:

- denormalized structures

- aggregation-friendly layouts

- analytical indexing models

- columnar storage alignment

- read-optimized execution paths

OLAP design emphasizes throughput, scan efficiency, and analytical performance.

Test Real Analytical Workloads with Exasol Personal

Unlimited data. Full analytics performance.

Star schema

Star schemas organize data around a central fact table connected to dimension tables. They optimize analytical query performance by simplifying joins and enabling efficient aggregation. Structural properties include:

- centralized metrics storage

- dimensional context separation

- simplified join topology

- predictable query patterns

Star schemas favor performance and query simplicity.

Snowflake schema

Snowflake schemas normalize dimension structures into hierarchical relationships. They reduce redundancy while preserving analytical structure. Structural properties include:

- normalized dimensions

- reduced data duplication

- increased join complexity

- improved data consistency

Snowflake schemas trade query simplicity for structural normalization.

Event-driven schema

Event-driven models represent state transitions as immutable event records. They define system behavior through event streams rather than mutable state tables. Structural properties include:

- append-only storage

- temporal ordering

- immutable data structures

- replayable state reconstruction

- auditability by design

Event-driven schemas support traceability, auditability, and temporal analysis.

Design patterns provide structural alignment between data architecture and system behavior. They encode architectural intent into schema structure rather than embedding behavior in application logic.

Modern Database Design

Modern database design extends beyond single-node systems and monolithic storage architectures. It operates across distributed systems, heterogeneous storage layers, and hybrid processing models that integrate transactional and analytical workloads.

Cloud-native architectures define systems built around elastic resources, dynamic scaling, and managed infrastructure layers. Storage and compute are decoupled, enabling independent scaling models, fault isolation, and resource optimization. Database design in cloud-native systems must account for network latency, distributed coordination, and failure domains as structural constraints.

Distributed systems introduce partitioned execution, data replication, and consensus models. Data placement, shard topology, replication strategies, and consistency models define system behavior under failure, load, and concurrency. Schema design in distributed environments directly influences fault tolerance, availability, and execution efficiency. System reliability in distributed architectures depends on distributed consensus mechanisms that coordinate state agreement across independent nodes.

Federated access patterns and cross-system query models enable unified analytical views across distributed sources, forming the structural basis for continuous intelligence architectures in large-scale data ecosystems.

Lakehouse models integrate analytical storage and operational access within unified architectures. They combine large-scale data storage with structured query processing, enabling hybrid workloads across historical and operational data. Design constraints include schema evolution, metadata management, query federation, and multi-engine interoperability.

Streaming architectures define event-driven data processing models. Data is ingested continuously, processed incrementally, and stored as evolving state rather than static records. Schema design in streaming systems must support temporal modeling, late-arriving data, reprocessing, and state reconstruction.

Streaming system design increasingly supports real-time analytics models that require continuous ingestion, low-latency processing, and incremental state updates.

Modern database design aligns structural modeling with distributed execution, elastic scaling, and hybrid workload processing. It defines systems as evolving architectures rather than static deployments, requiring schema structures that support adaptation, resilience, and long-term system evolution.

Test Real Analytical Workloads with Exasol Personal

Unlimited data. Full analytics performance.

Common Design Mistakes

Anti-Patterns

Design failures in database systems rarely originate from tooling limitations. They emerge from structural design errors that introduce long-term instability, performance degradation, and operational fragility.

Over-normalization

Excessive decomposition of schemas increases join complexity, execution cost, and query planning overhead. While normalization enforces structural correctness, uncontrolled fragmentation degrades performance, increases execution complexity, and amplifies dependency chains. Over-normalized systems trade integrity for operational inefficiency.

Under-normalization

Insufficient normalization embeds redundancy, dependency anomalies, and update inconsistencies directly into schema structure. This leads to data duplication, integrity drift, and semantic divergence across the system. Under-normalization compromises correctness for short-term performance gains.

Index abuse

Uncontrolled index proliferation increases write amplification, maintenance cost, memory pressure, and storage overhead. Indexes become structural liabilities when they are added without selectivity analysis, workload modeling, and access-pattern validation.

Schema rigidity

Rigid schema structures prevent evolution. Systems that lack versioning strategies, migration pathways, and compatibility models become resistant to change. Schema rigidity converts evolution into system risk rather than controlled transformation.

Hard-coded business logic

Embedding business rules into application logic instead of structural constraints weakens integrity guarantees. When validation, relationships, and dependencies are enforced procedurally rather than structurally, correctness becomes dependent on application behavior rather than system architecture.

These anti-patterns introduce compounding risk. They degrade system reliability, scalability, and maintainability over time, transforming structural design flaws into systemic operational failures.

Database Design Examples

Transaction System Example (OLTP Structure)

A transactional system is designed for high-frequency writes, concurrent access, and strict consistency guarantees.

Structural characteristics:

- normalized schema structure

- strict referential integrity

- short transactions

- high write concurrency

- low-latency point queries

- stable identity models

Example structure:

Customer(customer_id, name, contact_data, status)

Order(order_id, customer_id, order_timestamp, state)

OrderItem(order_item_id, order_id, product_id, quantity, price)

Payment(payment_id, order_id, payment_type, status, timestamp)

Design properties:

- primary keys define identity

- foreign keys enforce integrity

- normalization eliminates redundancy

- indexing supports point lookups

- transactional isolation preserves correctness under concurrency

This structure prioritizes correctness, consistency, and operational stability under high concurrency.

Analytics System Example (OLAP Structure)

An analytical system is designed for large-scale reads, aggregation, and historical analysis.

Structural characteristics:

- denormalized schemas

- aggregation-oriented modeling

- read-optimized layouts

- scan-efficient structures

- analytical indexing models

Example structure:

- SalesFact(order_id, product_id, customer_id, date_id, revenue, quantity)

- CustomerDim(customer_id, region, segment, industry)

- ProductDim(product_id, category, brand)

- DateDim(date_id, year, quarter, month, day)

Design properties:

- separation of facts and dimensions

- simplified join topology

- predictable query paths

- aggregation-friendly structure

- performance-oriented access patterns

This structure prioritizes analytical throughput and query efficiency over transactional normalization.

Test Real Analytical Workloads with Exasol Personal

Unlimited data. Full analytics performance.

Hybrid System Example (HTAP Structure)

Hybrid systems support both transactional and analytical workloads on shared data structures.

Structural characteristics:

- partially normalized core tables

- derived analytical projections

- shared identity models

- mixed workload execution paths

Example structure:

- transactional core tables for operational integrity

- derived analytical views for reporting

- replicated data segments for analytics

- isolated write paths for transactional stability

Design properties:

- workload separation

- execution isolation

- data duplication for performance

- controlled consistency boundaries

- parallel access models

This structure balances correctness, performance, and analytical accessibility.

Normalization vs Denormalization Example

Normalized structure:

- customer data stored once

- product data stored once

- relationships represented via keys

- minimal redundancy

- strong integrity guarantees

Denormalized structure:

- repeated customer attributes

- embedded product attributes

- reduced join operations

- faster query execution

- increased redundancy risk

This trade-off illustrates the structural balance between integrity and performance. Normalization enforces correctness. Denormalization optimizes access patterns. Both are structural design tools, not opposing philosophies.

Test Real Analytical Workloads with Exasol Personal

Unlimited data. Full analytics performance.

Lifecycle Management

Database design does not terminate at deployment. It defines a system that must evolve under changing requirements, growing data volumes, shifting workloads, and long-term operational constraints. Lifecycle management is therefore a structural design responsibility, not an operational afterthought.

Versioning

Versioning defines controlled change management for schemas, structures, and constraints. Schema versions formalize system evolution, enabling traceability, rollback capability, and controlled transitions between structural states. Versioning transforms change into a managed process rather than an operational risk.

Migration strategies

Migration defines how structural changes are applied to live systems. Data migration models, transformation pipelines, validation processes, and rollback mechanisms ensure that structural evolution does not compromise integrity, availability, or correctness. Migration is an engineering discipline, not a deployment task.

Schema evolution

Schema evolution defines how systems adapt without structural breakage. Additive changes, deprecation models, compatibility layers, and transitional schemas enable continuous evolution without system instability. Evolution is controlled adaptation, not structural replacement.

Backward compatibility

Backward compatibility preserves operational continuity across versions. Interface stability, data access consistency, and structural compatibility models ensure that dependent systems continue to function as architectures evolve. Compatibility is a structural guarantee, not a procedural workaround.

Lifecycle management defines the long-term stability of a database system. It ensures that structural correctness, performance, security, and integrity are preserved as the system evolves. A database is not a static artifact; it is a living architecture that must support controlled transformation over its operational lifetime.